Where Do Music Catalog Valuations Go From Here

How rising interest rates may impact the music IP M&A market.

GM readers 👋,

Happy April! I’ve been writing a lot of strategy pieces the past couple months. In this newsletter, I’ll be turning up the nerd factor a bit 🤓 with more numbers and math. Like many finance folks, I’ve been thinking about inflation and rising interest rates a lot recently. How might valuations and financial returns be impacted? More specifically, I’ve been approached by more than one investor and potential seller with this question, as it relates to music catalogs. So, let’s dust off the ‘ole financial modeling skills and explore: where do music catalog valuations go from here?

Note: None of this is financial advice. Do your own research!

Two final items before diving into the post:

A few weeks ago, a destructive tornado tore through my hometown of New Orleans, Louisiana, affecting many families in the community. If you’d like to contribute to relief efforts, consider donating here.

As Alderbrook scales, we are looking for part-time analysts who are skilled writers, financial modelers, presentation designers, and strategic thinkers. This is a flexible, paid role for individuals who enjoy helping companies of various sizes solve challenging problems. Bonus points if you are knowledgeable and passionate about the gaming, music, or Web3 industries. Please reach out to contact@alderbrookcompanies.com if you are interested in learning more.

Thanks again for reading. Now, let’s get after it!

Jimmy

PS if you have feedback on the post, as always, please let me know!

Where Do Music Catalog Valuations Go From Here?

“Pessimists sound smart. Optimists make money.” - Nat Friedman, Former CEO of Github

The global music catalog deal market has been on fire the past several years and 2021 marked a new high. Music Business Worldwide calculates over $5 billion was spent on music rights acquisitions in 2021. Meanwhile, Midia Research suggests that labels, PE funds, and other music rights investors spent a total of roughly $12 billion – more than double the 2020 total. As depicted below, the music catalog M&A market was quite small prior to 2018 with under $1 billion of deal activity annually.

Music catalog valuations have also been on an upward trajectory. According to an insightful report from investment bank Shot Tower Capital, music publishing catalogs are trading at an average multiple of 16x-20x+ net publisher’s share (“NPS” or a publisher’s gross margin) today – two times higher than the 8x-10x NPS multiple realized in the early 2010s. Likewise, recorded music catalogs, according to Shot Tower’s data, are trading at 12x-13x net label’s share (“NLS” or a record company’s gross margin) – two times higher than the 6x-7x NLS multiple realized ten years earlier.

What drove deal activity, valuations, and fundraising to explode over the past several years? Readers of this newsletter may remember I covered these drivers a couple years ago. As a reminder, they include:

The emergence of streaming leading to higher cash flow growth expectations: The emergence of streaming has brought greater stability to the cash flows associated with music rights. The recorded music industry, in particular, has benefited, with streaming driving a return to growth after a decade-plus of declines caused by piracy and the decline of CD album sales. There is now greater confidence in owning music IP assets and the royalty income derived from them. For example, Goldman Sachs expects the global recorded music and music publishing markets to grow at a mid- to high single digit percentage through 2030 (the below chart shows Goldman’s projection for the recorded music market). Compare that to year-over-year declines or low single digit growth 10 to 20 years ago. In this context, higher valuations make sense.

The recurring nature of music royalties: Music royalties are a source of recurring income. Music royalty income is collected by several different distributors, with income paid periodically to music IP rights holders. Recurring payments are desirable to investors looking for a source of predictable income, typically found in asset classes such as real estate.

The low correlation to economic activity: Music spending has historically shown little correlation to broader economic activity. Historically, both recorded music and music publishing data have not seen a clear correlation with broader spending activity. In the below chart, Goldman Sachs compares the recorded music industry’s 15-year decline due to piracy and its subsequent streaming-driven rebound versus personal consumer expenditures (“PCE”). Per Goldman, recorded music spending has outgrown PCE growth by a factor of 2.4x since 2016.

Attractive yields in an environment with low interest rates and dividend yields: Interest rates have remained at historically low levels. In the recent market environment, investors are searching for opportunities to earn something on their cash without a high risk of losing their principal. As a result, music royalties have been viewed as an attractive alternative, with mega asset managers – such as Pimco, KKR, Blackstone, Oaktree, and Apollo – all announcing plans to commit billions of dollars to music rights acquisitions in the past couple years.

What’s changed?

The first three drivers – higher cash flow growth, recurring income, uncorrelated to broader economy – continue to be true and supportive of valuations. However, the fourth driver – attractive relative yields – appears to be in the process of changing.

Along these lines, the US Federal Reserve raised short-term interest rates in March for the first time since 2018 to combat the highest inflation rate in 40 years. And the Fed expects to hike rates from its current target of 0.25% - 0.5% to 1.75% - 2% by the end of 2022. As a result, investors will likely be able to earn (in nominal terms) more on lower risk assets than they have been in the past few years.

For example, US Treasury yields and the Vanguard High Yield Corporate Bond (“VWEHX”) ETF yield are rising off their lows, standing at 2.4% and 4.7%, respectively (depicted below). Conversely, publicly-traded music catalog aggregator Hipgnosis Songs Fund’s dividend yield is currently 4.3%.

As investors are able to generate higher returns from “risk-free” US government bonds, their return expectations for higher-risk asset classes, such as music IP assets, will likely increase. Here’s the abstract academic logic:

A higher risk-free rate, which many analysts derive from the 10 year US Treasury yield, drives up the required return on capital (“r” in the formula below).

A higher required return on capital results in a buyer valuing the same asset at a lower price (“DCF”).

Simply put, higher interest rates should result in lower values for music catalogs, all else equal.

To help clarify this point, let’s look at a simple example. (Note: If you’re already familiar with discounted cash flow analysis, feel free to skip ahead two paragraphs 😊.)

If an asset generated $100 of income in the last twelve months; I expect it to generate $500 next year (400% growth) and no more thereafter; and investors require a 10% return, then investors should be willing to pay $454.54 or 4.5x the last twelve months’ income.

$454.54 = $500 / (1 + 10%)

But if interest rates rise causing investors to now require a 20% (instead of 10%) return but cash flows do not change, investors should be willing to pay $416.67 or 4.2x the last twelve month’s income.

$416.67 = $500 / (1+ 20%)

Now, let’s look at a real world example of songwriter performance royalties. In this example, a catalog that includes a partial interest in Vanessa Williams’ Grammy-winning “Save the Best for Last,” sold via Royalty Exchange, an online marketplace to buy and sell royalties. As a reminder, at a song level, new music royalty income generally sees its greatest income 3-12 months after release. Income then declines over the next 5-10 years. At this point, the remaining “tail” of income often bounces around but remains relatively stable thereafter.

“Save the Best for Last” was released in 1992 and makes up 91% of the catalog’s last twelve months of income, implying that we’re analyzing years 25+ (i.e., the typical “tail”). As you can see, the catalog’s quarterly income bounces around between $1,500 to $2,000 consistently.

In order to help illustrate the impact of higher interest rates, let’s create a simplified discounted cash flow model to evaluate what a buyer might be willing to pay for this catalog under different growth and discount rate scenarios. We’ll use the following assumptions:

All catalog income is received by the buyer (i.e., there are no incremental administration expenses).

The buyer’s tax rate = 21%.

The purchase price can be amortized over 10 years.

The catalog grows into perpetuity at a rate of 2% per year. (Note: 2% is an arbitrary growth rate. In general, though, most individual catalog steady-state growth rates are lower than industry growth rates. This is because industry growth rates take into account new content (i.e., songs) coming into the system, whereas static catalogs do not. That said, I’ve seen acquisitions that appear to underwrite these “Wall Street” growth estimates when calculating a catalog’s purchase price. If that’s the case, those buyers may eventually realize their underwritten growth assumptions were too high.)

The buyer’s weighted average cost of capital (i.e., discount rate) = 10%

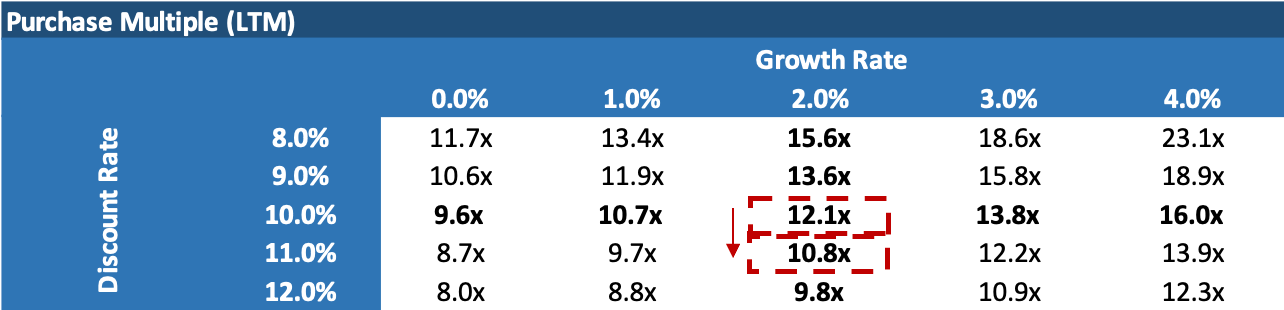

Given these assumptions, a buyer should be willing to pay $77,707 or a 12.1x multiple of the catalog’s last twelve months’ income. However, if we instead assume that the buyer’s cost of capital increases from 10% to 11% due to inflation and rising interest rates, the buyer would only be willing to pay $69,764 or a 10.8x multiple – a 1.3x decrease in purchase multiple in order to achieve a 1% higher rate of return on their investment.

Let’s look at a sensitivity table of purchase multiples for this catalog, in which we vary the discount rate and cash flow growth rate. For each 1% increase in a buyer’s cost of capital, the purchase multiple declines 1x+, assuming no change to catalog growth rates. There is also a larger multiple contraction for buyers that have lower discount rates or assume higher growth rates. In other words, buyer’s need to believe that cash flow growth will accelerate – approximately 100 basis points – in order to be willing to pay the same purchase multiple.

We can also look to the public markets for another example of the potential impact of rising interest rates on catalog valuations. For example, Hipgnosis Songs Fund has its catalog independently valued when reporting results. As of September 30, 2021, the company’s independent valuer used a discount rate of 8.5% to calculate a portfolio value of $2.55 billion or a 19x multiple of annual NPS income. Per Hipgnosis, a 0.5% increase in its discount rate would result in a ~$200 million or ~8% reduction in its net asset value, implying a 17.5x multiple of annual NPS income. In short, small increases in the assumed cost of capital – without any change to underlying cash flow growth rates – can have large implications on music catalog valuations.

There is also one other potential implication of rising interest rates on the music catalog M&A market – rising borrowing costs. Many catalog buyers borrow funds to acquire these assets, in order to increase their rate of return to equity investors. Typically, catalog buyers opt to borrow from the cheapest form of capital, which is usually commercial banks. That said, interest on bank debt is usually quoted as a floating rate, such as LIBOR, and resets every few months. The three-month LIBOR rate (depicted below) is rising off recent lows. So then, as interest rates rise, the interest burden of music catalog buyers will also increase.

In addition, banks often require borrowers to maintain certain financial metrics in order to remain in compliance with the loan agreement. For example, a borrower may only be able to borrow 30% of the total value of their catalog, as calculated by an independent valuer. In a situation where interest rates are rising and catalog values are falling, buyers who are already highly levered become at risk of breaching these loan agreements. This can force buyers to allocate cash flow that might otherwise be used to acquire new catalogs to repay borrowings and/or to sell assets to service borrowings.

In summary, rising discount rates – caused by higher inflation and interest rates – could have a material adverse impact on music catalog valuations, at least in the near-term. At the same time, higher borrowing costs may impact buyers’ ability to acquire new catalogs, reducing the size of the potential buyer pool.

How Might Valuations Remain Unaffected?

In my opinion, it is looking more and more likely that discount rates will rise in the near-term. But that’s not to say a decline in music catalog valuations is inevitable. Cash flow growth may accelerate to (more than) offset the potential impact of rising interest rates. In order to see how this works mathematically, let’s return to our earlier “Save the Best for Last” example. If a buyer’s discount rate increases from 10% to 11%, cash flow growth needs to accelerate from 2% to 3% (with our assumptions) in order for a buyer to be willing to pay the same 12x purchase multiple.

The required increase in growth to maintain the same purchase multiple may sound small. But in my experience, music catalogs are not high growth assets, with “steady state” catalogs growing 0% to 4% (if not, declining) annually. So, while each music catalog is different, underwriting additional growth to pay the same multiple is often a risky proposition, at least historically.

That said, things may change in the future. It’s entirely possible that “steady state” catalog cash flows see higher growth rates than I currently expect. Along these lines, some potential levers to higher than expected cash flow growth include:

Higher streaming subscription prices. Spotify has been testing price increases in certain territories. Amazon Music also just announced plans to increase prices. Higher prices will mean a growing pie for rights holders. Of course, the risk is that higher prices meaningfully impacts subscriber churn rates.

Alternative platform revenue. I recently published a piece about how the recorded music industry may be on the cusp of change. My thesis is that recorded music rights will likely continue to benefit from partnerships with gaming and technology companies – like Epic Games, Bytedance, Roblox – in addition to the emergence of novel Web3 use cases, such as non-fungible tokens. Along these lines, a few weeks ago, IFPI, the organization that represents the global recorded music industry, reported recorded music industry revenues increased 18.5% in 2021. This figure was above Goldman Sachs’ 2021 growth estimate. That said, individual catalog growth rates are not the same as those for the industry as a whole.

Statutory rate changes for music composition rights. Whereas master recording royalty rates are negotiated in the free market, music composition rates paid to songwriters and publishers are typically set by a statutory review process. There are several music composition rate changes that are currently being fought over. These include a potential rate increase for the physical mechanical royalties paid to songwriters and publishers. In addition, songwriters and publishers may see an increase in interactive streaming royalty rates.

In short, it’s possible that cash flow growth expectations shift enough to offset higher interest rates. After spending time as a long/short hedge fund analyst, I learned the hard way that forecasters are rarely right, and am often reminded by a much smarter friend that “Pessimists sound smart. Optimists make money.”

What are the implications?

But what if cash flow growth doesn’t accelerate enough to offset higher interest rates? The implications of rising rates for the music catalog market will likely impact various rights holders in different ways. In my opinion, the rights owners that are best positioned for this scenario include:

Traditional labels and publishers over catalog aggregators. Traditional labels and publishers are in the business of releasing new music and their growth can more closely track industry growth. Meanwhile, aggregators do not focus on releasing new music, typically placing greater focus on acquiring and managing catalog rights and distributing associated cash flows to investors. As a result, labels and publishers are more likely to experience the incremental growth necessary to offset rising rates. I also wouldn’t be surprised if catalog aggregators look to allocate more capital to their frontline businesses.

Master recording rights holders over musical composition rights holders. As discussed, music composition rates are typically statutory. As a result, the rate setting process can be slow, filled with uncertainty, and often does not reflect market realities. Along these lines, a Harvard study showed that music composition mechanical rights did not keep up with inflation between 1976 to 2010. On the other hand, master recording rights holders are able to negotiate rates in the free market. This allows for more frequent negotiations and a greater likelihood of cash flows adjusting to higher inflation rates (assuming rights holders have sufficient negotiating leverage).

Companies with low leverage & fixed-rate debt over those with high leverage & floating-rate debt. As interest rates rise, borrowers with higher debt burdens and floating interest rates will be more adversely impacted. I’d expect companies with floating rate debt to look to mitigate this risk via interest rate swaps, where possible / warranted.

Final Thoughts

In a low interest rate environment, cash flowing music IP assets have been viewed as an attractive asset class. Over the past few years, deal activity has reached all-time highs. However, rising interest rates may have a significant impact on music valuations going forward. If buyers require higher rates of return going forward, catalog cash flows need to accelerate, in order to maintain the same purchase multiples. As a result, the next 6 to 12 months will be interesting to watch.

Thanks to Hannah and Adam for the feedback, input, and editing!

Well done, Jimmy!

Question on the DCF valuation: isn't the DCF valuation a function of depreciation and depreciation is a function of value? How do you go about this?

Apologies for my ignorance, would be great to see a quick calc or backup excel.