A Rake Too Far? Spotify & the Music Middle Class

“The problem is that since the dawn of streaming, the [digital streaming] services themselves have sought to be seen as more than a music delivery service, and they have resented paying the songwriters who make their services possible – taking them to court time and time again and often blaming record labels for their inability to pay more. This breakdown makes clear that the money is there, they just expect to keep more of it for themselves.” - David Israelite, Head of the National Music Publishers Association

In this article, we discuss a contentious topic that has been debated in the music business for some time. Do digital service providers (“DSPs”), such as Spotify, pay rightsholders – record labels, publishers, artists, and songwriters – a “fair” amount? It will focus our attention specifically on how music’s middle class – those creators outside the top 1% to 2% – are faring in the streaming world.

Next, it considers from a high level whether this issue is unique to music. We currently live in a golden age for digital marketplaces that connect suppliers of content or goods with prospective consumers. For example, marketplaces, like Apple’s App Store, Uber, Airbnb, Alibaba, and eBay have become some of the most impactful and valuable companies in the world. What price (“rake” or “take rate”) is charged to suppliers on non-music marketplaces vs. those on music ones, like Spotify? Are the same income concentration issues present on these platforms too? Or is this entire discussion unique to the music industry?

The title of this essay is an ode to venture capitalist Bill Gurley’s famous blog post “A Rake Too Far: Optimal Platform Pricing Strategy” published in 2013. Per Gurley:

“In a casino the term “rake” refers to the commission that the house earns for operating the poker game. With each hand, a small percentage of the pot is scraped off by the dealer, which in essence becomes the “revenue” for the casino.”

So, spoiler alert! This article suggests that there is much to be learned from studying how non-music platforms price and work with their marketplace participants.

Finally, the article looks at potential solutions for fostering music’s middle class.

The goal is to unpack a controversial topic by looking at it from a variety of angles, including at other industries outside of music. We are drawing on our experience investing and researching music assets and companies as well as our work in other sectors, such as video gaming and technology. But this essay also relies on the ideas and contributions from leaders across relevant industries who have explored the issues at hand and advocated for more equitable opportunities for creators. And we have done our best to give them credit where it is due throughout this piece.

Let’s dive in!

The Debate: Do music streaming services pay rightsholders a “fair” amount?

Many music industry participants and commentators have covered the debate about how the music streaming pie is split. We’ll summarize this debate by reviewing i) how much music streaming platforms, like Spotify, pay rightsholders and ii) how much actually makes it to creators (i.e., artists and songwriters) after their labels and publishers are paid. This is important because a music creator can experience multiple levels of “rake.” The first layer occurs when the DSP takes their fee. The second occurs when the creator’s record label or publisher takes their cut. [Note: This discussion will not delve into what collection agencies – such as Harry Fox, ASCAP and BMI – rake.]

What do music streaming platforms, like Spotify, pay rightsholders?

Here’s the quick math:

There are roughly 3 million creators on Spotify

Spotify generated €1.9bn ($2.4bn) of revenue in 3Q 2020

Spotify pays major record labels (e.g. Warner, Universal, Sony) 52% of net receipts attributable to their artists and 10.5% to music publishers and songwriters

On Spotify, the top 43,000 artists – roughly 1.2% on the platform – earn 90% of royalties and make, on average, $25,990 per quarter

The remaining 2.957 million creators – roughly 98.8% on the platform – earn the remaining 10% of royalties and make, on average, $42 per quarter

If we assume the top 43,000 artists were also credited as the only writer on their songs (often not the case), they would make, on average, $31,238 per quarter

Assuming the same for the remaining 99%, they would make, on average, just $50 per quarter.

This is important because streaming made up 80% of recorded music industry revenue in 2019 and continues to gain share. Outside of touring and merchandise income (we’ll come back to this later), streaming is the main driver of music creator income.

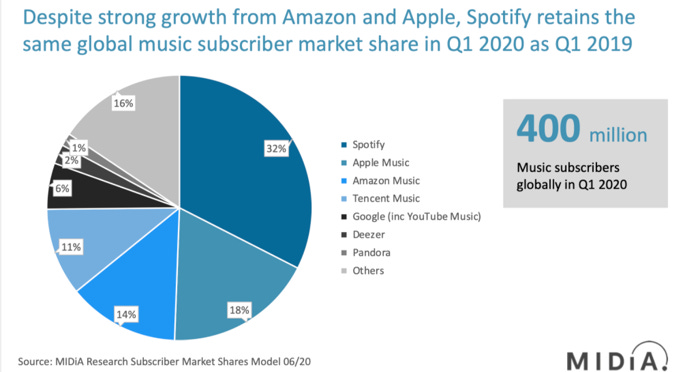

Of course, there are other streaming platforms where creators can earn income, but Spotify is the biggest audio streaming service, making up 32% of subscribers worldwide, as illustrated in the graph below.

And streaming royalties aren’t much better elsewhere with most DSPs paying less than a penny per stream to rightsholders. Goldman Sachs estimates the average payout per stream from the top three streaming services (Spotify, Apple, and Amazon) is only $0.006 per stream to rightsholders.

Even if we were to gross that estimated $50 per quarter up to 100% across all streaming services worldwide (generous because content consumed in many international markets, like China, is mostly that country’s local repertoire[1]), music rightsholders outside the top 1% to 2% would earn, on average, an estimated $157 per quarter from streaming. And, as venture capitalist Li Jin points out, music creators would need over 3 million streams per year at the per stream rates on Spotify to achieve the $15,080 annual earnings of a full-time minimum wage worker. Compare that figure to the 52% of US adults living in middle income households that earned $48,500 to $145,500 in 2016.

What actually ends up with artists and songwriters?

As discussed, the first “rake” is what DSPs, like Spotify, charge rightsholders to distribute their music on the platform. At Spotify, this is currently about 37.5%. But there is also a second layer of pie splitting. This is what labels and publishers charge artists and songwriters if they sign a recording and/or publishing deal. Labels and publishers often receive 50% to 85% of royalties paid to rightsholders, which equates to a 30% to 50%+ “rake” on music streaming services’ gross revenue. (Again, there can be another layer of rake from collection agencies – such as Harry Fox Agency, ASCAP, BMI, etc. – that administer licenses on behalf of rightsholders, but these are not considered in this analysis.) After the DSP and labels/publishers are paid, this leaves about 10% to 35% of every dollar spent on digital streaming services for artists and songwriters.

All this helps explain why Goldman Sachs estimates artists typically generate 30% to 70% of their income from live performances. This is important in the context of COVID-19, as the pandemic has all but stopped the live music industry. Goldman estimates that for every $10 consumers spend on a concert, $6 to $7 goes to the artist compared to only $1 to $2 on a streaming platform.[2] This concept is reflected in the diagram below. It is important because it implies that the average earnings per creator on Spotify, highlighted in the prior section, is overstated by 2x to 5x after factoring in label and publishing splits.

With that said, some artists and songwriters are independent, meaning they avoid label and publishing splits. We are generalizing to a degree. And labels and publishers are typically making an upfront payment (“advance”) and other investments (e.g., marketing, recording, etc.) to support the growth of an artist and/or songwriter’s career. The terms of these deals are driven by the fact that the label or publisher is often making a risky investment, especially when the creator is unproven with a small following. In short, we are not suggesting that labels and publishers do not play a part in increasing a music creator’s pie over time. Regardless, we think it’s important to acknowledge both the streaming platforms’ rakes and the labels/publishers’ splits in this discussion.

Contextualizing the Debate: Music platforms vs. non-music platforms

Since COVID-19 began to impact all our lives, the discussion of how music content platforms compensate creators has picked up steam. This is in part because: i) artists and songwriters – unable to tour due to the pandemic – have announced that they are selling their intellectual property rights, because they can’t make ends meet on streaming payments alone; ii) in a challenging period for creators, Spotify’s stock price nearly tripled in ten months, as more people socially distanced and entertained themselves with streaming services; iii) Spotify and other DSPs are appealing a court ruling that increases what they pay songwriters in the US; and iv) the UK government has begun to review how and what music streaming services pay rightsholders.

So, how does Spotify’s rake compare to other digital platforms?

As mentioned at the beginning of this article, many digital marketplaces charge a “rake” or “take-rate.” In the US, Spotify’s rake is driven by free-market negotiations on the master recording side and by government regulation on the musical composition side. Between its 52% payout to labels and artists and 10.5% payout to publishers and writers, Spotify’s take-rate is estimated at 37.5% of revenue.

For comparison, the chart below shows rakes across digital platforms. The chart shows a wide range of take rates – from 3% (Shopify) up to 70% (Shutterstock). You can also see very high rakes in the case of the Apple App Store and the Google Play Store (two companies that run two of the largest music streaming platforms). It is important to note that these rates are estimated based upon publicly available information.

As illustrated above, Spotify’s 37.5% take-rate lands at the high end of the distribution. If Spotify and other music DSPs lose their Copyright Royalty Board (“CRB”) appeal, songwriters and publishers will eventually see their share of streaming revenue rise from 10.5% currently to 15.1% over the next few years. This means Spotify’s take-rate may fall to 32.9% depending upon the final CRB decision. Even still, music streaming platforms, like Spotify, receive a relatively high rake compared to other digital platforms.

But that is not the end of the story. Remember if a creator is signed to a label or publisher, there is another layer of pie-splitting (first the DSP and second the label/publisher). Things begin to look even more harrowing for creators after the label/publisher split, with an estimated total rake of 65% to 90% (depending upon contract terms) before creators are paid.

Is the income inequality problem unique to music content platforms?

Next, let’s contextualize the income concentration on music DSPs. As previously discussed, the top 1% or so of Spotify creators earn 90% of the royalties. Is this issue unique to music? Or do similar dynamics exist on non-music content platforms?

In her recent essay “Building the Middle Class of the Creator Economy,” venture capitalist Li Jin highlights a 1981 paper by Sherwin Rose, an economist at the University of Chicago. The research paper explains how the “superstar phenomenon” would become more pronounced as a result of technology. In a market with different providers, success is disproportionately concentrated at the top with technology exacerbating the problem via lower distribution costs. The best performers are no longer limited by physical constraints like a concert hall and can now satisfy an unlimited market demand: “lesser talent often is a poor substitute for greater talent [...] hearing a succession of mediocre singers does not add up to a single outstanding performance.”

Indeed, income concentration at the top is seen across various digital content platforms. For example, on Patreon, only the top 2% of creators made the federal minimum wage of $1,160 per month in 2017. The trend holds true in video games, as well. Electronic Arts product lead Ran Mo describes how income concentration on the online gaming platform Roblox – recently valued at $29.5 billion – has grown over time, even as usage increases:

“The top Roblox game in 2018, “Jailbreak”, accounted for roughly 8-10% of all concurrent users on the platforms (though numbers vary depending on the day). Today, the top Roblox game “Adopt Me” accounts for upwards of 20-25% of all concurrent users on the platform. This concentration is even more striking when accounting for Roblox’s growth over the past two years.”

Mo’s account is reflected in the graph below.

In summary, the issue of income concentration on music streaming platforms is not unique and is, in general, experienced across other types of digital content platforms.

So, is creator income inequality inevitable on music streaming platforms?

Tim Ingham, founder of Music Business Worldwide, recently published a piece about the income inequality debate. His conclusion:

“Welcome to the extremely harsh reality: The vast, vast majority of artists creating music today, around 99% of them, are never going to make enough money from streaming to live on. Ever. A tiny minority of artists, the 1%ers (nudging towards the 2%ers), will make enough to live on. This is not a situation created by Spotify. It’s not even a situation created by the major record companies. It’s a fact of life based on the only people who matter: the fans, and what they choose to listen to. Cruel bastards.”

Perhaps this view is correct. Income inequality is likely on Spotify and other music streaming platforms. Not everyone can be a platinum selling musician. On the other hand, there are examples of a creator middle-class on digital content platforms. And, as Tim Ingham points out, the number of artists earning 90% of total royalties on Spotify is growing, increasing to 43,000 artists in June 2020 from 30,000 (or up 43%) artists in June 2019.

So even if income concentration is inevitable, music streaming platforms should be focusing on providing as many pathways as possible for artists and songwriters to succeed. In doing so, the number of creators earning a living wage on these platforms can continue to increase over time. Importantly, this is not just a social or ethical discussion. For each music DSP to flourish, creators and their partners (e.g. labels and publishers) have to feel that they are able to grow their audiences and achieve financial success on the platform. Otherwise, they will be incentivized to migrate to another, more open platform.

Potential solutions for supporting the Music Middle Class

What are some strategies and initiatives that can be implemented to help facilitate and accelerate the transition towards more music creators being able to earn a living wage? This section pulls from the ideas of thought leaders in the music and tech industries, in an effort to bring their expansive knowledge in the arena together under one umbrella.

Music digital service platforms can charge a lower rake. Lower take-rates can flow – at least in part – to creators’ pockets. Given where music DSP take-rates currently stand in the context of other digital platforms, appealing the latest CRB decision seems short-sighted. It is interesting that Apple was one of the few DSPs that chose not to appeal the CRB ruling. Notably, the implied pro forma take-rate for Apple Music will still be higher than the 30% take-rate Apple receives from developers on its App Store.

Most music streaming platforms likely disagree with this suggestion – hence appealing the CRB rate increase – and that reaction is not surprising. First, music streaming, pioneered by Spotify, has allowed the global recorded music industry to return to growth after more than a decade of declines. Second, Spotify’s stock price has outperformed the S&P 500 by 100%+ during the past twelve months. Finally, the company is not yet consistently GAAP earnings profitable, so paying rightsholders a higher take-rate will decrease the company’s margins, all else equal. This will make its path to profitability more difficult in the short-term, which would likely negatively impact the company’s share price. In short, from a music platform’s strategic and economic point of view, it is fair to ask why change what seems to be working?

Even still, there are likely longer term strategic benefits to be had– in addition to the social ones we laid out previously – from closely aligning with creators and the three largest music rightsholders (Warner Music, Universal Music, and Sony Music). As a reminder, the majors collectively hold 68% and 58% shares of the recorded music and music publishing markets. Venture capitalist Bill Gurley notes how aggressive take-rates can negatively impact long-term partnerships. Ironically, he uses Apple’s – the DSP not appealing the increase to US songwriting streaming royalties – relationship with Facebook and Amazon as an example:

“Specifically, two companies that potentially could have helped to reinforce the success of the iOS platform blinked, paused, and then went on to support a competitive platform. Both Amazon and Facebook could have been and should have been BFFs with Apple. And if Apple could go back in time, they would surely opt to be BFFs also. The most threatening company for all three players was clearly Google… When Facebook and Amazon read the terms of service of the iOS platform, and came to grips with the reality of the 30% rake, they saw an instant road-block… It was very hard to imagine their business model and Apple’s business model coexisting, and so they eventually punted on a full commitment to iOS. The bottom line is they could have been amazing partners. If Apple had a lower rake, or even had they been less obstinate about their existing rake, a partnership could have formed (ask anyone in Hollywood – “splits” can solve any problem).”

It makes you wonder if Apple, Google, and/or Amazon – profitable technology firms who operate popular music platforms, in part, to bring and keep users into their larger ecosystems – will eventually decide to lower their take-rates. After all, Amazon’s Jeff Bezos is credited as saying, “Your margin is my opportunity.” Lower pricing could open the door for exclusive partnership opportunities with the largest music suppliers on their marketplaces, as each platform tries to differentiate and compete for users.

Reduce the rake for lower earning creators. Music streaming platforms take-rates are a fixed percentage of revenue and do not adjust for an individual artist’s or songwriter’s earnings. One potential solution to support lowering earning creators is a tiered system where the platform’s rake decreases as a creator’s income decreases.

This is not a novel idea. The US federal income tax rate increases based upon an individual’s income bracket. Among internet platforms, Apple recently announced it will reduce its 30% App Store rake to 15% for developers earning less than $1 million in annual net sales. However, some platforms, such as video game distribution platform Steam, actually reduce rakes as earnings grow.

Test decoupling royalties from market share. Currently, music platforms pay royalties based upon a creator’s total share of all streams on a platform. For example, if Taylor Swift gets 5% of everyone’s streams on Spotify, Swift (and her label/publisher) gets 5% of your Spotify subscription regardless of whether you listen to any of her songs. Several industry pundits, such as Chris Castle, argue that platforms should adopt a user centric approach to support smaller and more niche creators. While it remains unclear how a user centric payout system will actually impact income concentration on music streaming platforms, a Finnish Musicians Union academic study suggests that top-tier artists would not receive higher payouts, and in general, lower earning creators would receive more income. Another study by the Centre National de la Musique and Deloitte found that streaming revenues for classical music would rise 24% with a respective drop in rap and hip-hop revenues of 20%+. French music streaming service Deezer has said they want to run a user centric pricing system pilot to assess the actual impact on payouts.

Allow artists to monetize their superfans. Kevin Kelly’s classic “1,000 True Fans” outlines the potential power of the creator-fan relationship. If a creator receives $100 per year from each true fan, then she only needs 1,000 of them to earn $100,000 per year. Subscriptions and fan donations (among other features) can enable artists to make meaningful amounts.

For example, on video streaming service Twitch, fans can purchase $4.99, $9.99 and $24.99 per month subscriptions to their favorite streaming channel. As Li Jin points out in the same article cited earlier, if each Twitch subscriber counts for one view, its monetization rate is 1,000x more than music streaming platform’s current $3 to $10 per 1,000 streams. In April 2020, Spotify added a feature for fans to pay artists directly. Time will tell how this feature grows.

What are other ways streaming platforms can help artists monetize their fans? MIDiA Research’s Mark Mulligan has written about how Chinese music streaming companies, such as Tencent Music Entertainment, have been innovators in helping creators tap into the “fan economy” with live streams, virtual gifts, and virtual currencies.

Recommend new and niche content with an element of randomness. One theory on why income concentration exists on digital platforms is that users only search for what they know and most recommendation systems recommend what other users are consuming. This results in users rarely seeing anything outside of their bubble. As popular creators are further amplified, the middle class struggles to gain awareness. However, algorithmic recommendations can help new and niche artists. TikTok’s recommendation system uses several signals, including content that users haven’t seen before, in order to allow users to “discover new creators, and experience new perspectives and ideas as you scroll through your feed.”

Spotify’s “Discover Weekly” playlist uses algorithmic recommendations as well. Its recommendation system relies on a listener’s unique preferences and other users’ consumption patterns. Spotify intends for this weekly playlist to highlight “fresh jams and deep cuts.” Hopefully it incorporates an element of randomness to do so, truly opening the door for undiscovered artists to be heard.

Offer a form of ongoing creator support. In response to COVID-19, governments and platforms supported those whose livelihoods were impacted by the pandemic. The U.S. passed the CARES Act which provided $1,200 per adult direct cash payments. In Austria, the government established a 90 million euro fund to provide 15,000 freelance artists with 1,000 euros per month for six months. Music streaming platforms also stepped up to help creators. For example, Apple Music launched a $50 million fund for independent labels and their artists, and Spotify established a $10 million fund to help artists.

Why would music platforms implement continued support post-pandemic? It may be a strategy to incentivize more creators to devote time to creating music content. As Li Jin notes in her essay, 71% of Americans prefer self-employment over being an employee, but financial considerations are the main impediment to making the leap. TikTok’s $200 million Creator Fund appears to be focused on this issue:

“The US fund will start with $200 million to help support ambitious creators who are seeking opportunities to foster a livelihood through their innovative content. The fund will be distributed over the coming year and is expected to grow over that time.”

As seen previously, the music industry had mixed reactions when Spotify launched a no up-front cost direct distribution program. This could be an opportunity for streaming platforms to work in partnership with labels and publishers to support up-and-coming creators.

Provide creator education and training. Platforms can facilitate learnings and provide suggestions on best practice for artists and songwriters to be successful on the platform. For example, the On Deck Fellowship provides creator education and community for podcasters and writers to grow their audiences and earnings on the platform. This could be yet another opportunity for partnership between platforms and labels/publishers.

Labels and publishers can offer creators better splits too. It is not just the music platforms that rake a large percentage of streaming revenue. Label and publishing splits contribute to why such a small percentage of total streaming revenue ends up in creators’ pockets. Positive steps do appear to be happening on this front. For example, BMG recently noted that its new recording contracts improve splits in favor of creators:

“Since [artists and songwriters] are the principals, they should receive the lion’s share of revenue, hence while traditional record companies pay royalties of 20% or less, our new recording deals credit recording artists with 70% of revenue or more. We don’t do this because we are do-gooders. We do it because we believe that’s the logic of the streaming revolution and the modern way to do things.”

Working towards more artists & songwriters earning a living wage

Music streaming platforms openly speak about a world where there is a healthy music middle class. For example, Spotify clearly states its mission statement in its annual financial filings each year:

“Our mission is to unlock the potential of human creativity by giving a million creative artists the opportunity to live off their art and billions of fans the opportunity to enjoy and be inspired by these creators.”

To realize this vision, music streaming platforms and labels/publishers have to balance this desire with several realities:

1) Music streaming platforms currently receive a relatively large percentage of streaming economics compared to other types of digital platforms.

2) Labels and publishers also receive a relatively large percentage of streaming economics despite streaming distribution costs being lower than in the physical (e.g., CDs, cassettes) era.

3) Digital platforms are, by their nature, set-up so that tremendous leverage accrues to top creators at the expense of smaller, up-and-coming, and niche creators.

Making sure there is a path for more artists and songwriters to earn a living wage is a challenging one. But it’s an incredibly important path to create. Fostering ecosystems, where every artist has a shot to succeed, is crucial from both a social and strategic standpoint.

[1] Goldman Sachs, “Music in the Air: The Show Must Go On”, May 2020.[2] Goldman Sachs, “Music in the Air: The Show Must Go On”, May 2020.